As any electrician knows, it’s very straightforward to trace cables… providing you can see them. As soon as they’re buried in walls or under floor spaces, finding cables becomes a laborious combination of educated guesswork, luck and dogged persistence, aided by an insight into whatever was going on in the crazed mind of the person who installed them in such a bizarre topology.

Cable finders such as the Martindale CD1000 and CEM CLS20 claim to put an end to all your cable-finding problems. But do they deliver all they promise? And which should you spend your money on: the CLS20 (currently £119 + VAT), or the CD1000 (£259 + VAT)?

Applications

From the advertising copy, you might believe that cable finders are the answer to all an electrician’s prayers. However, before we get too carried away, let’s start with the idea that a cable finder injects a signal into a cable, and detects that signal elsewhere, providing the receiver is within a few centimetres to metres of the cable. This gives you a pretty good idea of what it can actually be used for:

- Finding where an unseen cable is laid

- Locating a break in a cable (where the signal stops due to electrical separation)

- Locating a short in a cable (where the signal stops due to looping back down a return conductor)

- Locating the fuse supplying a live circuit where it can not easily be isolated

- Working out the topography of connections between multiple points (break the cable at the junctions, then trace each cable to the next point)

- Finding underground cables - providing they don’t have earthed sheathing, as they invariably will

- Tracing metallic pipes, providing they are not earthed

What a cable finder won’t do is:

- Magically tell you the exact path of a single cable without having to isolate it electrically from others

- Be entirely specific (think of a sniffer dog following a scent trail, or in worse cases a medium contacting the spirits of the dead)

- Trace cables running through earthed sheathing, or earthed metallic conduit

- Trace earthed metallic pipes

Cable Finder Theory: Class 101

A cable finder is, in principle, a straightforward device. A transmitter uses a cable as an antenna or loop, injecting a digitally modulated AC waveform down it (or modifying the existing AC waveform, in the case of a live cable). This creates a precisely alternating electromagnetic field around the cable. A receiver then detects this field when it is in proximity to the cable. By changing the waveform, you can, if desired, discriminate between different transmitters (although you’d have to purchase multiple transmitters separately). By changing the power of the transmitter, you can change the sensitivity and discrimination of the reception.

The signal transmitted down a cable will be stopped by a break in the conductor, or a short to the return conductor. This means that when the signal stops, you’ve found the break in the cable, or the short circuit. You can also find the fuse connected to a live circuit if it’s not possible to isolate it.

Cable finders rely on capacitance between two conductors - usually the conductor in the cable you’re trying to find, plus earth - or a loop of conductor. The first case is one-pole mode, where the transmitter is connected to a good earth elsewhere (not the CPC of the same circuit), and to the conductor to be found, or if this is not possible, to two unlinked conductors of the same cable.

The second, looped, case can be used with live or dead cables. When testing a dead cable, the loop can be created by joining two conductors at their distant end (rather as in R1+R2 resistance testing). If a short exists between two conductors, this in itself will create a loop. With live testing, line and neutral conductors can be used, as they are effectively a loop, joined at the transformer. This is known as dual-pole mode.

One-pole mode is useful for tracing wiring and finding interruptions (such as a break in a cable), or buried cables (where the damn plasterer has plastered over your metal boxes again). Cables can be traced to a depth of 2m or more, depending on the equipment used. Dual-pole mode is useful when tracing live cables, or fuses or MCBs for circuits which cannot be isolated; or when tracing low-impedance short circuits in dead cables.

The effectiveness of the device is impacted by the quality of the capacitative coupling between the cable and earth (one-pole), inductive interference between two neighbouring conductors in the same cable, length of cable, cross-feeding between different cables due to induction and crossover, strength of source signal, proximity to signal, shielding by other materials, and other factors. Turning the transmitter power up may allow you to find a cable more easily, but it will also markedly increase the crosstalk to other cables, meaning unless they are well isolated and not in parallel runs, you may not detect what you think you’re detecting.

Manufacturers like to talk about detecting underground cables; unfortunately, most of the time these will be SWA cables, which are well shielded by their own earthed armour, and therefore undetectable unless you are able to isolate the armour from earth at both ends (in which case you can treat the armour as a traceable conductor in itself).

Consequently cable finding is more of an art than a science. Don’t expect a device which will reliably buzz when you’re above the cable, and stay quiet in every other situation. Anybody who has ever used a metal detector in a field and found endless ring pulls and no gold coins will know how this works in practice.

Out of the Box

Martindale CD1000 Cable Finder

The CD1000 is supplied in a fabric case containing a transmitter and receiver, neck strap for the receiver, cables and earth electrode.

The CD1000 is supplied in a fabric case containing a transmitter and receiver, neck strap for the receiver, cables and earth electrode.

Both transmitter and receiver are of reassuringly good build quality, and are also bright yellow, making them easy to find. Both feature LED torch functionality for convenience. The transmitter has a fold-out stand.

The electrode is provided for when you are using the device in one-pole mode, where you will need to make use of a good earth. Sometimes it may be easier to use the building’s own earth connection (local electrode or PME), but the Martindale electrode is supplied and ready to use if you want it.

The test leads provided have standard 4mm connectors at the device end, but terminate in non-removable prongs, with crocodile clips provided that slip over the prongs as a sleeve. In practice this means that if you want to connect to any other standard connection device (such as a Kewtech Kewcheck R2 3-pin adapter, or your preferred crocodile clips or probes of choice) then you’re out of luck. I’d rather have seen Martindale ditch the earth electrode and provide double-ended 4mm leads with interchangeable probes and croc clips. I wonder whether Martindale are trying to push customers towards their own-brand SB-13 3-pin adapter, but this also takes standard 4mm leads so the logic here isn’t clear.

For a device which is likely to live in the back of a van, a hard case would be good to have instead of the soft case supplied. You’ll probably want to budget to buy a separate hard case if you want to prolong the life of the device.

Batteries are provided; for reasons I’m not entirely clear on, one device uses 6x AAA (9V) and the other a PP3 (also 9V), so you’ll have to carry both types as spares. There is no calibration certificate for the voltmeter function, which means this aspect can be used as an indicator but not a test instrument.

CLS20 Cable Locator

The CLS20 creates a good impression from the outset, arriving in a sturdy plastic case with precisely pre-cut foam to carefully house the separate components, including transmitter, receiver, cables, crocodile clips and probes. I’m a fan of this approach as it’s a good way to keep the device in excellent condition throughout its life, and also means you can easily see if you’ve left a component behind.

The CLS20 comes with double-ended standard 4mm test leads, which means it can be connected to the probes or crocodile clips provided, or a standard 3-pin socket breakout device such as the Martindale SB-13 or Kewtech Kewcheck R2. This is a thoughtful approach, as in the event of losing a probe or croc clip, you can use any industry standard connector or borrow one off another test meter.

Batteries are supplied; both transmitter and receiver take 9V PP3 batteries, so you only need a single type as a spare.

Both transmitter and receiver seem solidly built but do not come across as such a premium brand, with a dull blue colour and slightly dated screenprinted graphics. (Importer test-meter.co.uk tells me this will be updated shortly.) The receiver features a useful LED torch function, but not the transmitter.

The manufacturer provides a calibration certificate for the voltmeter function (when connected to the transmitter leads); consequently it can be used as a measuring instrument if required.

The CLS20 manual has been translated most probably from Chinese, and could do with a re-write, quite honestly. The importer, test-meter.co.uk, is aware of its inadequacies and this issue may be rectified in future.

In Use

Martindale

The Martindale transmitter is the more complex of the two, given its greater feature set. It has separate buttons to select power on/off, mute, torch feature, start/stop transmitting, select level, select code and adjust values up and down.

When powered on, the device visually confirms output level and code, and will display voltage if connected to a live cable. Pressing the Start/Stop button begins transmitting. Output level can not be changed while transmitting, and hence to change from low to high signal level takes 6 keypresses, rather than the 2 of the CLS20.

When powered on, the device visually confirms output level and code, and will display voltage if connected to a live cable. Pressing the Start/Stop button begins transmitting. Output level can not be changed while transmitting, and hence to change from low to high signal level takes 6 keypresses, rather than the 2 of the CLS20.

The transmit channel can be changed easily while the device is powered on, unlike the CLS20 on which the channel can only be set at power-on.

The receiver works automatically when powered up, and has separate buttons for backlight/mute, torch, manual mode, non-contact voltage (marked Uac), and manual level adjustment. Non-contact voltage mode can be used to find any live cables with no transmitter present.

The manual mode is aimed at enabling discrimination at the receiver end without changing the transmitter power. For example, cross-talk between cables may result in the receiver detecting signal from two adjacent cables. Switching to manual mode and turning the sensitivity down to a lower setting may show that the signal is stronger in one cable than the other. This can also be used to help narrow down which fuse or MCB in a consumer unit is on the end of the cable being tested, and exactly where a break in a conductor can be found.

The receiver display indicates auto detect, or discrimination level for manual detection, channel received, and the level of signal received. The level of signal is also indicator by an auditory tone which varies in pitch with the signal level. This can be muted.

CLS20 Cable finder

The transmitter is simplicity itself, having two buttons, one to turn it on and off, and the other to vary the output between 3 levels. The screen displays which level is being used. The device transmits constantly when on, and the output level can be changed during transmission.

The level button also activates a backlight when held down, and can be held when the device is powered up to alter the transmit channel between 7 possible options. If connected to a live cable, the transmitter will display the cable voltage as well as a warning triangle.

The level button also activates a backlight when held down, and can be held when the device is powered up to alter the transmit channel between 7 possible options. If connected to a live cable, the transmitter will display the cable voltage as well as a warning triangle.

The receiver is only slightly more complex. The NCV button turns the receiver into a non-contact voltage detector. There’s a button for the torch, and a button to switch between automatic and manual modes, with arrow keys to adjust the sensitivity.

The display shows a visual representation of the received signal strength, while an auditory tone changes in pitch according to the strength of the signal. The tone can be muted, which is just as well as it’s on the irritating side, albeit very useful when not in polite company.

To use the device, connect the transmitter to the cables and turn it on; it starts transmitting instantly at low power. Press the Level button to change the transmitter power to medium or high levels or cycle back round. To stop transmitting, turn it off again. The receiver works as soon as you turn it on; manual mode (for discrimination) and Non-Contact Voltage mode are just a button press away.

Lab Testing

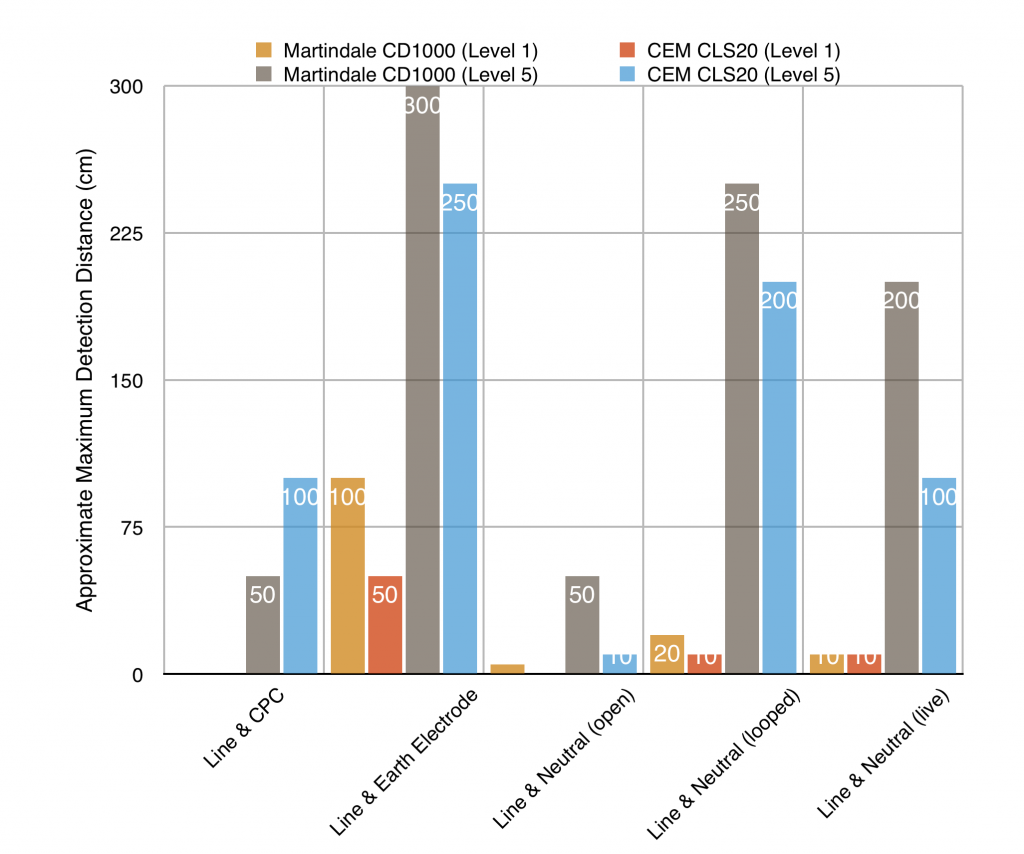

In order to test the devices in a directly comparable way, I set up both on a test rig consisting of a 5 metre length of 4mm² twin & earth cable, suspended in free air. I connected the CPC through to the supply earth, and configured the cable so I could connect it directly to the supply at one end, and bridge line & neutral cables at the far end (although obviously not at the same time). The supply was a TN-CS type, with no local earth electrode.

I tested both devices in one-pole mode using a direct connection to the CPC, and separately using the earth electrode supplied by Martindale. I also tested dual-pole mode. The connection arrangements I tested were:

Dead: line & CPC, line & earth electrode, line & neutral (isolated), line & neutral (looped)

Live: line & neutral

Note that when using line & CPC, I did not earth the neutral conductor as recommended by both manufacturers. This should improve range if applied.

In each configuration I moved the receiver along the length of the cable, gauging at several points the furthest distance the receiver could be from the cable and still receive a signal. This varied along the length of the cable, perhaps due to standing waves varying the strength of the field; I recorded the approximate minimum value.

The least reliable and useful connection was dead testing using line cable & CPC, which at the lowest transmission setting was patchy at best, with the receivers sometimes unable to detect the signal even when touching the cable sheathing. The greatest range was achieved using line cable & earth electrode. This is surprising in a way, given that the CPC is connected to the mass of earth, and I can’t honestly say I understand the exact reason behind this; an RF engineer I consulted didn’t have an immediate explanation either, but no doubt the words “capacitance” and probably “inductance” come into it somewhere.

Overall, the Martindale tester had a greater range than the CLS20 in several circumstances, but not in every situation.

It was noticeable that the CLS20 tended to pick up a signal fairly instantaneously when the receiver came in range of the transmitter, whereas the Martindale’s response lagged behind, taking a second or two to detect even a strong signal. This may become frustrating when using the Martindale in situations where it’s necessary to sweep the receiver around to find the cable.

Real World Testing

I first had the chance to try out both cable finders when a chippie helpfully buried some sections of a ring main behind plasterboard.

First up, the CLS20. I connected it to the next socket in the ring using a Kewtech Kewcheck R2, using line and neutral cables; I knew the cable depth was less than 10cm through plasterboard, and it was easier to do this than to run a trailing lead to earth. I switched the transmitter level to 2 and pointed the receiver at the area of the wall in question.

By sweeping the receiver from side to side I was quickly able to locate the general area of the cable. Slow movements whilst monitoring the signal strength on the display helped me narrow this down. Use of the manual mode to discriminate more finely gave me a 10cm target area.

The CLS20’s auditory output wasn’t as useful as I’d hoped, simply because the pitch change was not significant over the variation of signal strength as I got near the cable.

I repeated the test with the Martindale. It took a few more button presses to get the transmitter outputting at level 2, but it was hardly an odious task. The Martindale’s display was a little clearer than the CLS20’s, but most usefully, the auditory output had a greater range of discrimination, making it somewhat easier to narrow down the position.

Not surprisingly, both cable finders gave me the same cable position, but I was puzzled as to why I could only narrow this down to a 10cm band. Drilling a pilot hole through the plasterboard answered this when I hit the joist. (The wall was lined with Sellotex so my stud detector was useless.) I drilled a couple of inches further right, and found the cable - but not as I was expecting. It turns out the chippie, in his wisdom, had looped my cable and trapped it between the joist and plasterboard, so I actually had two bits of the same cable, one length either side of the joist. Drilling the other side of the joist led me to what I was looking for. This explains why I was only able to pinpoint the cable to within a 10cm region; I was receiving signal from two roughly parallel sections of the same cable, 10cm apart.

In this instance I was unlucky, as I ended up drilling 3 holes, but had it not been for the loop in the cable, I reckon I’d have hit it bang on first time. Time to get the filler out. Either way, it was a lot easier than drilling a pilot hole and sticking an endoscope camera into the void, which in any case was part filled with Sellotex.

I also used the cable finders when running a cable through a ceiling cavity. I was able to run a cable rod through the cavity via a small aperture, but wanted to locate the end of the rod exactly in order to drill a hole for the cable exit.

I taped a length of twin & earth to the cable rod, then looped line to neutral precisely at the end of the rod. I ran both rod and cable into the cavity, then connected the Martindale to the line and neutral wires at the other end of the cable, and set it to low output mode. Sweeping the receiver around the expected location enabled me to locate the end of the cable (and hence the rod) to within 60mm or so; I then switched to Manual mode and discriminated down to approximately 20mm - certainly accurately enough to be able to drill and hit the target within the aperture of the drill hole.

Again, repeating the test with the CLS20 highlighted that while setup is very straightforward, the auditory tone variation isn’t as user-friendly as the Martindale’s when trying to fine-tune the location. However, both devices did the job well and with similar accuracy, which potentially saved me considerable time and several holes in a ceiling.

Conclusions

I set out to answer two questions: are these devices useful? And which is the better of the two tested?

I’m left in no doubt that a cable finder is indeed a useful piece of equipment, providing it’s regarded as a tool to facilitate cable finding, rather than one to give clear, unambiguous answers or which can be used effectively by an unskilled operator out of the box in any circumstance. If you’re searching for a short or break, or trying to locate a hidden cable run, using a cable finder will invariably be a better solution than ripping out plasterboard and dismantling walls. However, achieving a successful result will still need forethought, patience and careful execution.

Regarding the devices tested, both are decent, well-built pieces of equipment, and I can easily find reasons to commend both of them.

The Martindale wins out on features, signal reliability and greatest range, which is not unexpected given it is more than double the price of the CLS20. However, I’d like to see it come with more versatile test leads, and a hard case; you’ll want to budget the cost of these into your purchase.

The CLS20 works impressively well for an entry-level unit, and is the more straightforward of the two to use. It comes well-equipped and ready to deploy. In use its reception is slightly more patchy than that of the Martindale, and in general its range is not quite so great. The manual is not easy to understand at the time of writing.

For somebody expecting to use a cable finder as an occasional but useful tool, who wants to throw it in the back of a van and hook it out a few times a month, the CLS20 ticks a lot of boxes and is undoubtedly a good buy. The more frequent user, who is looking for a more professional level tool and can justify the cost hike, will find it worthwhile to spend the extra for the Martindale’s increased flexibility and range.

Many thanks to www.test-meter.co.uk for providing both units for review.

Written by David French, Devonia Electrical